Australia’s most enviable natural asset is positioned to become the region’s green energy powerhouse for the Asia region, combining vast land, abundant solar resources, and growing political momentum.

The Western Green Energy Hub (WGEH) — a $100 billion mega-project — is set to transform 2.29 million hectares of remote Western Australia into one of the world’s largest clean energy precincts. Think 70 gigawatts of wind and solar. Think green hydrogen and ammonia exports. Think a new town built from scratch. This isn’t just a project — it’s a paradigm shift.

Environmental scrutiny is high, as it should be.

The WA EPA has called for a full Public Environmental Review, citing potential impacts on marine life, karst systems, and native fauna. The federal EPBC referral is now open for public comment, with stakeholders watching closely.

Backed by InterContinental Energy, CWP Global, and Mirning Green Energy Ltd, WGEH is more than steel and silicon. It’s a vision for a post-carbon economy, with Indigenous leadership at its core. The Mirning people, traditional custodians of the land, hold a 10% stake in the venture — a landmark move in economic inclusion and cultural stewardship.

The project could offset up to 22 million tonnes of CO₂ annually, making a serious dent in Australia’s emissions profile.

Image: Intercontinental Energy, Western Green Energy Hub and Korea Electric Power Corporation sign MOU towards a Joint Development Agreement for the production of green hydrogen in Australia.

The numbers are staggering: 3,000 wind turbines, 60 million solar panels, and up to 35 renewable energy “nodes,” each capable of powering entire cities. These nodes will feed electrolysers producing green hydrogen — the clean fuel of the future — destined for export markets in Asia and Europe.

The project will encompass the Eucla township with a population of 37 as of 2021 census – which will grow to a new town of approximately 8,000 workers.

Complete with electric buggies, vertical farms, and community hubs – WGEH isn’t just about electrons and molecules. It’s about people. The Eucla new town model for sustainable living, is designed to thrive in one of the country’s most remote regions.

There are active mineral sands exploration projects of titanium and zircon in the broader Eucla Basin, notably by McLaren Minerals.

The economic upside? Monumental. Tens of thousands of jobs across construction, operations, logistics, and manufacturing. Billions in export revenue. A boost to local supply chains and infrastructure with local manufacturing (e.g. solar panels, wind turbine components) and development of port infrastructure and desalination facilities to support exports.

The Nullarbor’s Western Green Energy Hub reduces reliance on fossil fuel exports and opens new markets in green hydrogen, ammonia, and clean tech services.

For Future Now Green News readers, this is one to watch. It’s got scale, story, and serious climate impact. Whether you’re in cleantech, policy, or just dreaming of a greener tomorrow, the Western Green Energy Hub is the kind of bold thinking that could position Australia as a renewable energy hub for the Asia region.

But What Are The Scientists Saying?

Ecologist Dr. Stefan Eberhard, a leading expert on karst systems, has renewed calls for the Nullarbor to be nominated for World Heritage listing, citing its vast underground cave networks, sinkholes, and endemic species found nowhere else on Earth. Beneath the flat terrain lies Australia’s largest limestone karst system, with over 4,500 mapped features — including caves stretching up to 35 km long. These fragile formations are highly sensitive to vibration, groundwater changes, and surface disturbance. The WA Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) has acknowledged the complexity of the proposal, requiring a Public Environmental Review after receiving 259 submissions calling for deeper scrutiny.

The Nullarbor Plain, located in southern Australian, contains a vast arid limestone plateau as the world’s largest area of exposed karst, and hosts hundreds of shallow caves- featuring dense accumulations of mostly Early Pliocene speleothems which provide a unique opportunity for documenting the detailed hydroclimatic history of the Pliocene Southern Hemisphere subtropics. Speleothems have been forming on Earth for at least 400 million years. Nature Scientific Report.

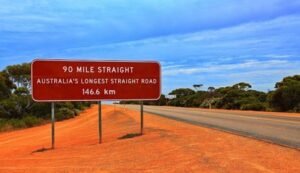

Where is the Nullarbor?:

The Nullarbor is a vast, arid, and largely treeless limestone plain in southern Australia, spanning from Ceduna (South Australia) to Norseman (Western Australia) of 1,200 kilometers. Named from the Latin for “no trees,” it is the world’s largest exposure of limestone bedrock, featuring unique landscapes like extensive cave systems, the dramatic Bunda Cliffs, and stretches of Highway One. Key attractions include the Nullarbor National Park, known for its karst landscapes and southern right whales, and the Nullarbor Links golf course, the world’s longest golf course.