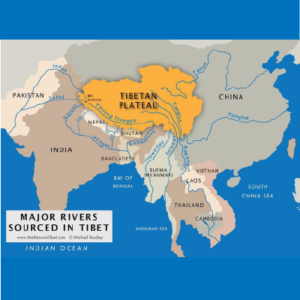

It is estimated that each year, 718 billion cubic meters of surface water flow from the Tibetan plateau and the regions of Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia, administered by China, to neighbouring countries.

The Tibetan plateau named the “Third Pole” – in which China has asserted outright ownership and in effect an upstream regulator – is due to its extensive glaciers and abundant freshwater reserves which supply nine countries from South Asia’s most powerful rivers: the Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Irrawaddy, Salween, Yangtze, and Mekong flowing into India, China, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam. Creating the largest river runoff from any single location.

More recently, following border clashes between India and China in the Galwan Valley, China blocked the flow of the Galwan River, an Indus tributary originating in the Chinese-controlled Aksai Chin area, thereby altering the river’s natural course to prevent it from entering India.

India must evaluate how China might “weaponize” its advantage over downstream countries. Control over these rivers effectively gives China a stranglehold on India’s economy.

In the absence of a mutually agreed dispute-resolution mechanism for water sharing for the cross-border rivers, and with China’s public refusal to submit to international dispute settlement, India has limited diplomatic solutions at its disposal. The primary recourse remains the effective management of domestic rivers and rainwater.

A regional alliance could collectively impose economic sanctions and negotiate with China for any upstream violations, in cooperation and fair use of shared water resources – with India and other countries in South and Southeast Asia. The proposed “Southern Asian water information grid”, is an institutional framework for improved transboundary management of shared rivers.

China has the potential to manipulate these rivers in three distinct ways.

China can “block or divert” the rivers. A power bargaining to neighboring countries. China’s extensive infrastructure projects, such as the South-North Water Diversion Project and West-East Power Transfer Project, already pose a threat to this.

Furthermore, to satisfy its irrigation and power requirements, the Chinese government planned to construct 120 gigawatts of new hydropower plants on the Salween, Upper Mekong, Upper Yangtze, and Brahmaputra rivers as per the Five-Year Plan 2011–15. This is equivalent to constructing more than one new Three Gorges Dam annually for the next five years, which is more than any other country has ever built.

Even in the region of Kashmir occupied by Pakistan, China has pledged to finance and construct five dams that will create the North Indus River Cascade. These dams will not only disrupt the water flow to lower riparian states, including India and Pakistan, particularly during non-monsoon months, but they will also halt the flow of silt that supports downstream agriculture.

China is also constructing five dams on the Brahmaputra river.

There are concerns that “directional blasting techniques” could be used to divert the Brahmaputra northwards to China at the u-bend before it enters India via the state of Arunachal Pradesh.

China has already obstructed the flow of the Xiabuqu river, a tributary of the Brahmaputra in Tibet, for the Lalho hydel project. More recently, following border clashes between India and China in the Galwan Valley, China blocked the flow of the Galwan River, an Indus tributary originating in the Chinese-controlled Aksai Chin area, thereby altering the river’s natural course to prevent it from entering India.

In the absence of a mutually agreed dispute-resolution mechanism for water sharing and China’s public refusal to submit to international dispute resolution, India has limited diplomatic solutions available.

Secondly, China could sabotage cross-border rivers by polluting them, making them unsuitable for use. The Siang river, which combines with the Lohit and Dibang downstream to form the Brahmaputra, became muddy and “blackened” in 2017, raising concerns about China’s upstream activities. The water became unfit for human consumption, with “up to ten inches of sediment accumulating on some stretches of the riverbed”.

This incident severely impacted agricultural production in the Siang valley, known as one of Arunachal Pradesh’s rice bowls in India, and also had a negative effect on fishing communities. Although China claimed that an earthquake in November 2017 might have been the cause, reports suggest that the river waters changed before the earthquake occurred.

Thirdly, China has access to valuable data that can assist in managing downstream floods and fluctuations. Since 2008, India and China have signed two agreements on data sharing for the Sutlej and Brahmaputra rivers to improve the management of shared watercourses. While these agreements have positively impacted water management and helped prevent and control flooding, this dependence can also be exploited by withholding hydrological data that is only accessible to the upper riparian state.

For instance, following the 73-day Doklam standoff between India and China in 2017, there were reports that China withheld hydrological data for the Brahmaputra and Sutlej rivers, in violation of the agreement. This resulted in floods in the states of Assam and Uttar Pradesh, causing the deaths of 300 people and displacing millions.

This isn’t the first instance where shared water bodies in the region have caused concern.

Alarmingly, in 2004, a lake started forming on the Parechu river, a tributary of the Sutlej originating in the Tibetan Himalayas, posing a flood threat to the lower regions of India’s Sutlej valley.

While China was cooperative and shared upstream data with India in advance, there was speculation (after China declined a request from India to send scientists and engineers to the site) that China intentionally created a “liquid bomb”, an artificial lake that could be released at will to potentially wreak havoc on downstream areas. Such fears of China possibly breaching and weaponising the waters of this Parechu lake resurfaced in June 2020, when a rise of 12 to 14 metres was noted in the river.

To be continued >>>>