Communities Rebuild and Innovate Following the January 2026 Northern Floods

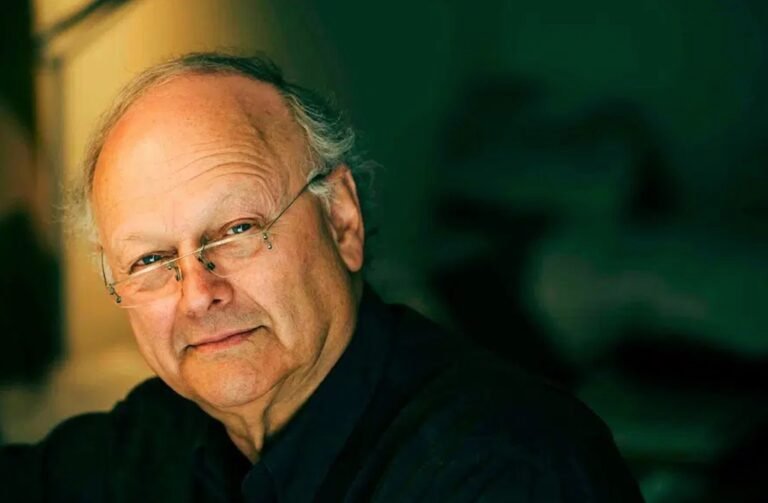

YASMEEN Lari, 83, is one of Pakistan’s most celebrated architects. As the country’s first certified female architect, she graduated from Oxford School of Architecture UK and became a Member of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in 1969 – and more recently, been awarded the prestigious 2023 Royal Gold Medal by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) for her work in zero-carbon, and self-build concepts for displaced populations.

Her career took a decisive turn after Pakistan’s catastrophic monsoon floods in 2022 submerged nearly a third of the country and destroyed hundreds of thousands of homes. Traditional mudbrick houses proved unable to withstand rising waters, leaving millions exposed to injury, illness and displacement. In response, Lari announced plans to raise funding for one million bamboo homes — each costing around US$100 — as Pakistan grappled with its worst floods on record.

Through the Heritage Foundation of Pakistan, which she founded with her husband in 1984 to preserve historic structures, Lari has helped deliver more than 50,000 shelters in flood-affected communities. Alongside this, she has been pioneering low-cost, climate-resilient housing built from locally available materials.

The urgency continues.

In late January 2026, northern Pakistan was hit by extreme cold and unseasonal rainfall and snowfall, with temperatures plunging from 5°C to –15°C. Torrential rain swept through the valleys of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Gilgit-Baltistan, triggering landslides and avalanches. Bridges collapsed, roads disappeared, and thousands of families were displaced as homes were overtaken by floodwaters. For communities already living with climate extremes, it was yet another reminder of how precarious daily life has become.

Pakistan has faced escalating climate risks for years

About 44.7 per cent of Pakistan’s population now lives below the poverty line, based on the World Bank’s updated 2025 threshold of US$4.20 per person per day for lower-middle-income countries. Repeated natural disasters have created waves of environmental displacement, with many families still waiting for permanent resettlement.

Lari’s work extends beyond housing.

Since 2017, she has been working with marginalised communities near Makli in Sindh, first connecting through conservation efforts at the fifteenth-century tomb of Sultan Ibrahim. Supported by grants from the US Ambassador’s Fund and UNESCO, the program trained more than 230 people across eight villages in pottery and ceramic crafts.

That work has since expanded to teaching women how to produce high-strength terracotta tiles, capable of withstanding more than 3,000 psi.

“They already make chapatis and work with dough,” Lari explains. “So they understand materials by touch — manipulating clay comes naturally.”

A Pioneer of Low-Cost Housing

Lari’s homes are built from bamboo frames raised on platforms, with earth and lime walls and reed mat roofs. These structures can withstand months of standing water and are built with skills that villagers themselves can learn and replicate.

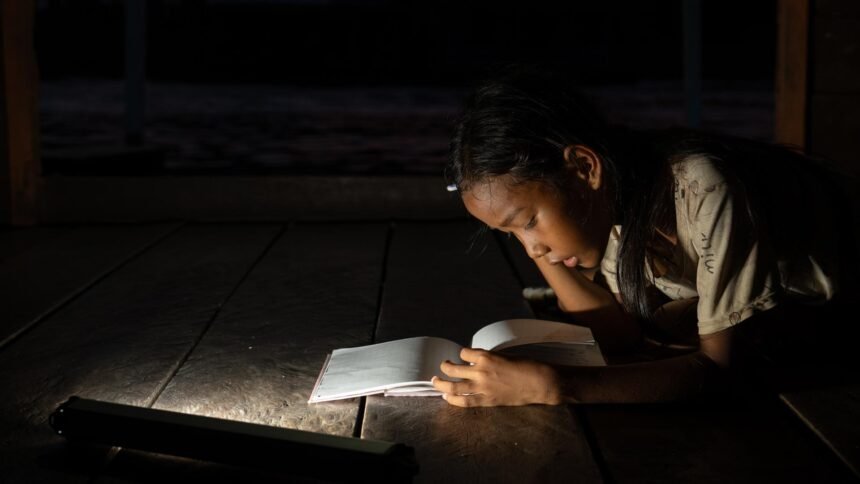

Residents actively participate in constructing resilient homes, learning skills for future disasters.

“They look like our traditional huts, but they stand where others fall,” said a resident of a village in Sindh that benefited from Lari’s designs. Her approach has already provided hundreds of families with homes that can survive floodwaters, protecting both lives and livelihoods.

For Devi, a resident of Wasram village, the impact was deeply personal. She lost her home in the 2022 floods. “At least now our children can sleep without fear,” she said, speaking about the bamboo home her family now occupies.

Training in construction techniques allowed Devi and her neighbours to actively participate in rebuilding their community, equipping them with knowledge for future challenges.

Young men like Jaman Rai, trained by Lari’s teams, have become local instructors, spreading resilient building skills further. “We are building for our future, not just for now,” Rai said, highlighting the social dimension of resilience that complements the physical structures.

CHECK OUT Sugarcrete’ 2024 Global Earthshot Prize Shortlist to “Build A Waste-Free World”

From heritage conservation to community livelihoods

Since 2017, Yasmeen Lari has been working with marginalised communities near Makli in Sindh, first connecting through conservation efforts at the fifteenth-century tomb of Sultan Ibrahim. With support from the US Ambassador’s Fund and UNESCO, the program trained more than 230 people across eight villages in pottery and ceramic crafts.

The work has since evolved to teaching women how to produce high-strength terracotta tiles, capable of withstanding more than 3,000 psi.

For many, the transition has been remarkably natural. Skills honed making chapatis and working with dough have translated easily to shaping clay — creating new livelihoods with minimal retraining and a strong sense of ownership over the process.

When the floods came again

Even as these communities adapt, the January 2026 floods in northern Pakistan underscored the scale of the challenge.

Flash floods, landslides, and cloudbursts swept through Buner, Shangla, and surrounding districts, catching residents off guard. Sher Nawab, a farmer from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, reflected on the event: “We have seen floods before, but not like this. The water came too fast, and there was nowhere safe to go.”

In response, humanitarian organisations and government agencies are mobilising support. The World Bank is providing financing for multi-hazard resilient housing, while local NGOs focus on WASH infrastructure and community-led training programs. Muslim Aid Pakistan has constructed more than 150 flood-resilient homes in Sindh and Chitral, with hundreds more planned for 2026. These homes include single rooms with washrooms, kitchens, and solar panels, blending safety, sustainability, and dignity.

Indus Earth Trust has also contributed by building houses in Balochistan with compressed earth blocks and bamboo, and training local masons to replicate these techniques. This approach ensures that resilience is not just top-down, but community-driven, with skills and knowledge retained locally.

Designing for place, culture and climate

Yasmeen Lari emphasises the importance of designing according to local conditions.

“You have to design according to the conditions where you are,” she said, explaining that effective climate-resilient housing cannot be imported wholesale but must respond to the environment and culture it inhabits.

For many families, these homes represent more than shelter — they are a lifeline. Residents speak of the security, dignity, and hope that resilient construction provides. As floods continue to test the limits of infrastructure and human endurance, Pakistan’s approach to climate-adapted housing illustrates the power of combining traditional knowledge, modern engineering, and community participation.

The January 2026 floods were a stark reminder that the climate crisis is ongoing.

Yet, through innovation and collaboration, communities are finding ways to not only survive but thrive. The new generation of climate-resilient homes across Pakistan demonstrates that resilience is built by people, with people, and for people, turning disaster into a blueprint for hope.

Find out more about The Heritage Foundation of Pakistan

Future Now Green News is a forward-thinking media platform dedicated to spotlighting the people, projects, and innovations driving the green & blue economy across Australia, Asia and Pacific region. Our mission is to inform, inspire, and connect changemakers through thought leadership and solutions-focused storytelling in sustainability, clean energy, regenerative tourism, climate action, and future-ready industries.