SINGAPORE will begin charging airline passengers and cargo operators a sustainable aviation fuel levy from April this year, with fuel uplift requirements taking effect from October 2026. Meanwhile, Japan’s refiners are pressing regulators to extend SAF obligations to airlines, and Thailand has begun production and warned output could be redirected without clear mandates.

Australia, by contrast, has yet to finalise the policy settings that would underpin domestic SAF production — despite demonstrating in May that its aviation fuel system can already handle SAF at scale, following the import and supply of nearly two million litres into Sydney Airport.

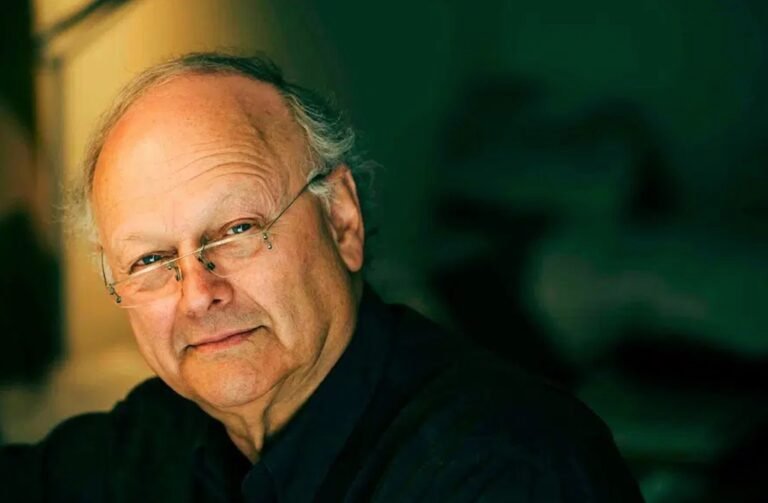

That policy gap framed Fiona Messent’s remarks at the Progress 2030 Summit in Melbourne late last year. The Group Chief Sustainability Officer of Qantas described sustainable aviation fuel as the most viable near-term pathway for aviation decarbonisation, but one that remains costly and risky in an industry defined by thin margins. Airlines can signal demand and co-invest selectively, she said, but cannot underwrite a fuels industry alone.

Australia has proven it can use SAF

The Sydney import was significant because it moved the discussion from aspiration to execution.

In early May 2025, almost two million litres of unblended SAF were shipped from Malaysia, blended at Ampol’s Kurnell facility, certified, and supplied into Sydney Airport’s fuel system. It was the largest SAF import Australia has handled to date.

The logistics worked with existing infrastructure handling the fuel without disruption. From an operational perspective, the trial answered a basic question: SAF can be moved through Australia’s aviation fuel system today.

What it did not answer is how often or at what price.

CHECK OUT AIR NZ SIGNS UP FOR 9M LITRES OF NESTE SAF FUELS

Asia is locking in demand through policy

Singapore’s SAF levy is designed to solve that problem. By pooling demand through a passenger and cargo charge, the city-state is creating a predictable funding mechanism for SAF uplift. Airlines will collect the levy and display it separately on tickets, making the cost transparent while guaranteeing demand.

Japan’s approach is still forming, but pressure from industry is explicit. In March last year, the head of Japan’s oil refiners group said regulations must also apply to airlines if the country is to meet its SAF targets. At the time, there were no mandatory SAF usage requirements for airlines, even as Japan works toward a 10 per cent SAF target by 2030.

Thailand offers a cautionary example. Bangchak began SAF production last year but has said long-term output will depend on the final shape of government mandates. Without them, production can pivot to renewable diesel — a commercially rational choice, but one that underscores how easily SAF supply can be redirected.

Across the region, the pattern is consistent: where demand is mandated or funded, production follows. Where it is not, capital hesitates.

Australia has funding, but not yet a market

Australia’s primary policy vehicle is the federal Cleaner Fuels Program, backed by $1.1billion in funding to support domestic low-carbon liquid fuels, including SAF and e-fuels. A policy design and consultation paper was released in November, with industry and legal analysis pointing to applications opening in mid-2026.

The funding commitment is real. What remains unresolved is the structure that will make projects finance-able over decades rather than funding rounds: whether through production credits, contracts-for-difference, blending obligations, or another demand-side mechanism.

That uncertainty is already shaping investment decisions.

Townsville puts 2026 on the calendar

Jet Zero’s proposed SAF refinery in Townsville has become the clearest test case.

The project received environmental approval from the Queensland Government in December and is moving toward a final investment decision in 2026. Public disclosures describe output of around 100 to 113 million litres per year, using agricultural waste and an alcohol-to-jet pathway.

The technical pathway is established, the site is approved, and the remaining question is whether policy settings will provide sufficient certainty for investors to commit capital.

If not, the project risks joining a list of well-advanced proposals waiting for clearer market signs.

What airlines can (and cannot) absorb

Messent’s comments were consistent with what airlines have been saying privately for several years.

SAF is expensive today and it carries technology risk. Airlines operate in a low-margin, high-cost environment, and there is a limit to how much premium cost can be absorbed without affecting competitiveness.

The Qantas Climate Fund is designed to play a catalytic role — investing selectively, sending demand signals, and supporting early projects — not to replace government or act as a refinery owner.

The Sydney import illustrated what airline action looks like at the operational edge. Scaling domestic production requires policy that spreads cost and risk beyond individual carriers.

Carbon markets remain a secondary tool

Messent also addressed the role of carbon markets. Even with efficiency gains and SAF scale-up, aviation will continue to face residual emissions through 2050. High-integrity carbon markets will remain part of the mix.

Qantas has established internal governance frameworks to manage integrity risk, including approved and excluded project lists. Offsets, however, are not positioned as a substitute for fuel transition. They sit behind it, filling gaps where technology and supply cannot yet deliver.

A narrowing window

Come mid-2026, several things will be visible.

Singapore’s SAF levy will be in force, Japan’s regulatory direction will be clearer, and at least one Australian SAF project will be seeking final investment approval.

Australia will either have a demand-side framework that reduces risk for domestic producers, or it will continue importing SAF from jurisdictions that do.

The Sydney shipment showed Australia can use sustainable fuel. The next phase will determine whether it chooses to make it, or remain a buyer in other countries’ policy markets.

By the end of this year, industry will be looking for answers. What price support will apply to domestic SAF? Who carries the premium — passengers, producers or government? How long will incentives last, and can they survive a change of policy cycle? And when Australia’s first projects ask for capital, will investors see a market… or just momentum?

Future Now Green News is a forward-thinking media platform dedicated to spotlighting the people, projects, and innovations driving the green & blue economy across Australia, Asia and Pacific region. Our mission is to inform, inspire, and connect changemakers through thought leadership and solutions-focused storytelling in sustainability, clean energy, regenerative tourism, climate action, and future-ready industries.