Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts. ~ Rachel Carson

AT dawn in rural Sabah, on the northern edge of Borneo, the soundscape arrives before the light. Frogs begin first. Then insects. Then birds, dozens of them, overlapping calls in what Didier Maraval describes as something close to orchestral. By nightfall, the rhythm changes entirely. Different species take over. Different frequencies. A second ecosystem clocking on.

Four years ago, none of this existed.

What now feels like a living sanctuary — dense with papyrus, bamboo, vines, insects, reptiles and birds — was once compacted, degraded paddy land. Yellow grass. Hydrophobic soil. Heat reflecting off bare ground. Flooding in the wet season. Almost no animal life.

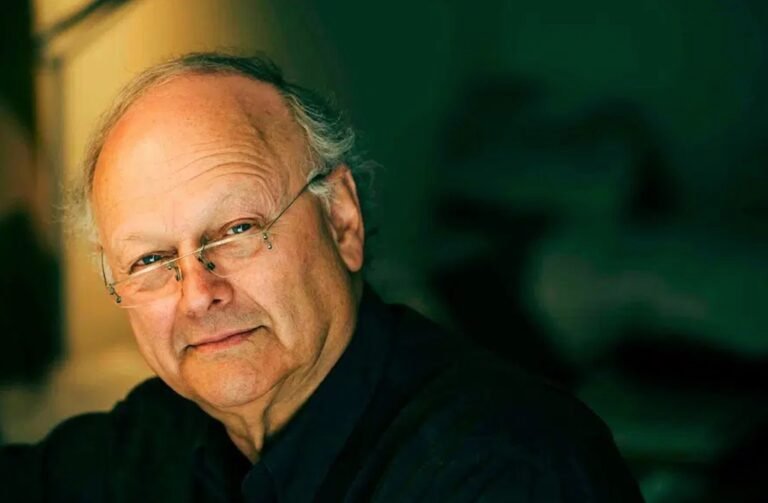

Today, Didier wakes each morning inside a functioning ecosystem. And he did it without consultants, capital, or climate-tech.

He did it by stepping back.

A house is not an object. It’s a system.

“For me, a house is not an isolated thing,” Didier tells me.

“It’s part of a living system. Soil, water, plants, animals, people — everything interacts.”

On his quarter-hectare site, built on former rice fields and surrounded by marshland, Didier practices what he calls a garden–forest approach. Waste becomes input. Organic matter feeds soil. Water is slowed and reused. Trees provide shade, food and microclimate. Structures adapt to the land rather than forcing the land to adapt to structures.

“The goal is not control,” he says. “It’s cooperation with natural processes.”

He stacks functions vertically, letting vines climb into canopy layers for light. He uses bamboo as wind protection. Drainage channels filled with organic biomass absorb floodwater that once pooled across the site. Compost systems and black soldier fly units turn food scraps into protein and fertile soil.

“This kind of ecosystem is never finished,” Didier says.

“It evolves.”

That principle sits at the heart of his work: regeneration is a relationship and not a product. For Didier, that relationship extends across everything on site.

“My project revolves around the holistic integration of all living systems — plants, animals, both domestic and wild, and humans,” he says.

“Only through truly harmonious integration does the work gain its full meaning and purpose. That perspective shapes every choice I make here.”

The moment everything changed

Initially, Didier planted giant papyrus around his land for one reason: protection.

Neighbouring areas regularly burn waste. Plastic smoke drifts across the landscape. Fires jump boundaries. The papyrus was meant to act as a living firebreak.

What followed surprised him.

Within months, biodiversity arrived — not cautiously, but in waves.

Birds. Small mammals. Dragonflies. Agamas. Lizards. Dozens of frog species. Pollinators. Predators. The marsh came alive.

“What struck me wasn’t just the species,” Didier says.

“It was the atmosphere. Day and night now produce two completely different soundscapes. Rich. Complex.”

That functional barrier became a refuge.

“When nature is given coherent, continuous space,” he reflects,

“it doesn’t respond timidly. It returns with force.”

That realisation reshaped everything.

Why he changed course

Didier’s move toward agroforestry and experimental farming began years earlier, deep in the Amazon, before his move to Borneo.

Before regeneration, he was a field herpetologist spending years working with snakes and reptiles, from anacondas and boas to Bothrops vipers and caimans. Curiosity eventually drew him toward Asia, in search of other ecosystems and species: pythons, gharials, and the mythical king cobra and its relatives.

What he encountered in Borneo came as a shock.

Vast stretches of rainforest had been replaced by palm oil monocultures, herbicides and pesticides saturated the landscape, and drainage canals between palm rows concentrated toxins, leaving wildlife with no alternative water sources. He began finding sick animals and, far too often, dead ones.

“That’s when everything changed,” Didier says.

Continuously rescuing or treating animals, only to release them back into a poisoned environment, no longer made sense. The problem was structural and not about individual animals. The root cause was land use and, more specifically, agricultural methods.

“So I changed direction,” he says.

He began studying permaculture, agroforestry and soil systems. He stopped focusing on emergency response and started rebuilding landscapes instead.

The aim was never symbolic sustainability.

Before/After: what regeneration actually looks like

Before…

Dry seasons brought scorching heat over bare, compacted ground. Trees were stressed. Animals were largely absent. The house overheated continuously.

Wet seasons were no better. Hardened soil repelled water, turning the land into slippery mud. Roots rotted. Flooding became routine.

After…

Pioneer trees and bamboo now cool the site year-round. Winds no longer sweep across the veranda. Metal roofing is protected from direct exposure. Chickens and dogs have reliable shelter from heat and rain.

Climbing vines spread food through canopy layers. Drainage channels filled with biomass absorb excess water. Compost and insect systems recycle nutrients. Medicinal herbs grow alongside vegetables and fruit.

Wildlife is no longer visiting. It lives there.

“Invasive plants that were once seen as problems now feed bees, butterflies, birds, squirrels and lizards,” Didier says.

“It’s a genuine explosion of life.”

On his quarter hectare, daily observation has replaced wildlife documentaries.

The ecosystem is present. Active and constantly evolving.

Didier is careful not to over-explain what he’s built.

“Details naturally carry power when they come from genuine situations,” he tells me. It’s why he shares sparingly — letting the land itself do most of the talking.

The biggest mistake in “sustainable” housing

Didier doesn’t mince words.

“One of the biggest errors is confusing high-tech with sustainable.”

He’s seen too many projects reliant on imported materials, deep concrete foundations and expensive systems that local communities can’t maintain.

“They create dependency, not resilience,” he explains, using plywood as a prime example. In tropical humidity, low-grade plywood absorbs moisture, becomes a breeding ground for fungi and insects, and disintegrates within years. Cheap short-term. Wasteful long-term.

He adds: “There’s also a tendency to design for image instead of for humidity, pests, maintenance, and daily use.”

In hazard-prone regions, Didier argues flexibility often matters more than rigidity. Lightweight bamboo structures can outperform heavy builds during earthquakes and floods.

“If a solution cannot be maintained without external money,” he says, “it is not truly sustainable.”

That line deserves to travel far beyond Borneo.

Waste is only waste if you ignore it

Waste, Didier believes, isn’t a problem. It’s simply a resource modern systems have forgotten how to use.

Sanitation and organic waste remain taboo in most development conversations, treated as inconvenient by-products rather than essential parts of ecological cycles. For Didier, they are foundational.

“If we ignore them, we create pollution, but if we manage them well, they become fertility,” he says.

On site, food scraps become protein for animals through black soldier fly larvae. Compost returns nutrients to soil. Water hyacinth cleans standing water while providing mulch and fodder. Biomass cycling replaces chemical inputs, closing loops that industrial systems routinely leave open.

“Regenerative practice,” Didier explains, “means looking at what society rejects and asking how it can become a resource.”

Low-tech works when it matches local ecology. Everything else, he says quietly, is branding.

He has taught permaculture in dozens of schools. He’s worked with villages and farmers. He speaks Malay. He’s lived locally for 15 years. And over that time, he has watched traditional knowledge steadily erode.

“People now trust commercial solutions that prioritise profit and standardisation. That makes nature-based systems harder to apply.”

Outside designers often underestimate humidity, termites, rodents, maintenance capacity — and human behaviour. As Didier explains, design that works on paper fails if it needs constant money, spare parts, or expertise people don’t have.

Real progress, he believes, emerges when development starts from local reality and improves it step by step — not when it arrives from elsewhere and attempts to replace it.

CHECK OUT CHINA: THE MIAO PEOPLE AND SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE

The personal cost of living inside your values

Didier currently has no income. As a foreigner in Malaysia, he cannot legally work without an expensive permit. His French bank account was closed. His pickup — once used to collect organic waste from markets — has been broken for four years.

Today, he grows food for himself and his animals. He harvests rainwater for cooking. He runs a rocket stove fueled by pruning wood and local biomass. Infrastructure is built from whatever materials are available on site.

His Malaysian wife covers electricity, internet, and dry food for the cats and dogs. Everything else is improvised.

“This level of precarity forces constant observation and optimisation,” Didier says. “There is no room for abstraction.”

He eats one meal a day. He experiments continuously.

“What this life gives me in return is direct feedback from the land,” he reflects. “Nothing theoretical survives long under these conditions.”

It isn’t romantic. It’s relentless. But it’s honest.

Why he stopped inviting visitors

Didier once opened his site to groups and individuals curious about regeneration. Every interaction ended badly. Some feedback was humiliating — not technical disagreement, but rejection of systems that challenged modern comfort norms.

He no longer accepts casual visitors.

“This place is root-level,” he says. “It requires humility, not spectatorship.”

Today, solitude feels safer than misunderstanding.

A message for policymakers and developers

His advice is disarmingly simple: Design with nature. Observe before building. Value local knowledge. Prioritise systems that can be repaired and understood locally.

Didier says: “Resilience is not bought… it is cultivated.”

Rachel Carson, a pioneering marine biologist and conservationist, warned more than half a century ago that humanity was sleepwalking into ecological collapse.

Didier isn’t writing books, he’s simply (but intelligently) rebuilding soil. On a forgotten edge of Borneo, without funding or fanfare, he’s proving something quietly radical: that regeneration doesn’t begin with technology.

It begins with attention. And with the quiet understanding that real change doesn’t arrive through grand gestures, but through details, lived daily, until they reshape the land.

Future Now Green News is a forward-thinking media platform dedicated to spotlighting the people, projects, and innovations driving the green & blue economy across Australia, Asia and Pacific region. Our mission is to inform, inspire, and connect changemakers through thought leadership and solutions-focused storytelling in sustainability, clean energy, regenerative tourism, climate action, and future-ready industries.