Why the Asian Century Demands We Lead, Not Follow

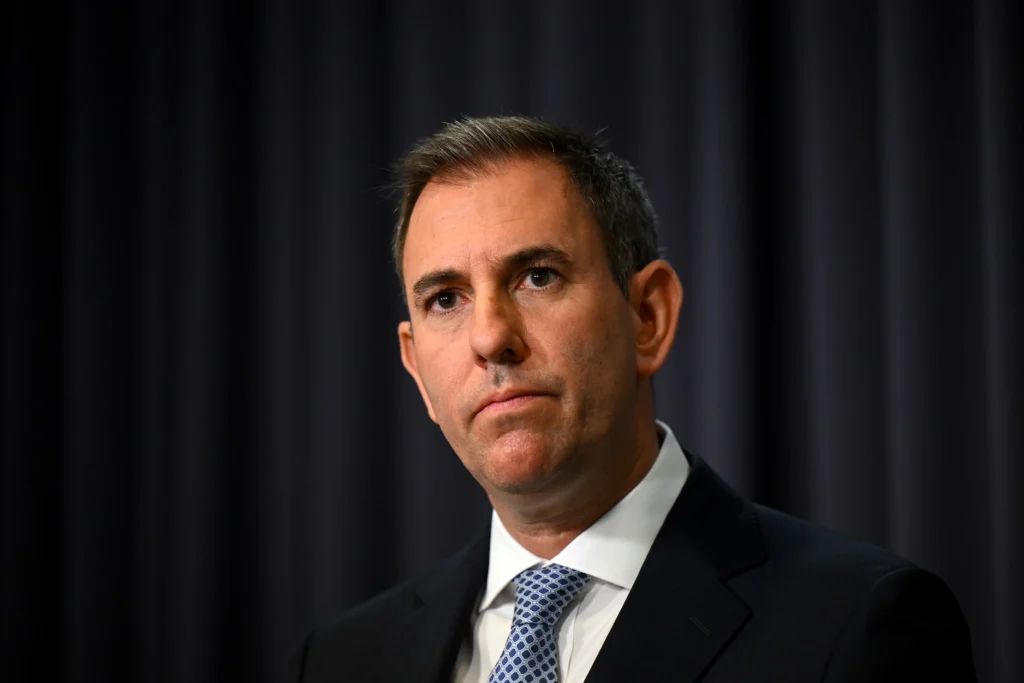

“Our job is to make sure we’re beneficiaries, not victims, of change.” ~ Jim Chalmers

WITH that line, calm, deliberate and freighted with intent, Australian Treasurer Jim Chalmers captured both the challenge and opportunity facing Australia as it charts a course through the defining forces of our time: artificial intelligence, climate transition, demographic transformation, and deepening regional interdependence.

Chalmers not only updated an economic scorecard in conversation at the Progress 2030 Impact Summit in Melbourne, but set out a national challenge that requires all of us to shed old assumptions about what Australia exports to the world, and ask how we build value from expertise, ethics, innovation and regional leadership.

For balance, this was not a speech delivered in a vacuum. Public sentiment towards Jim Chalmers is divided, a dynamic that echoed through side conversations and networking circles at the summit in the morning tea break.

While Chalmers presents himself as a reformist focused on cost-of-living relief, economic resilience and long-term productivity that has earnt praise from some quarters for his ambition and likeability, others view his approach as fiscally reckless, overly interventionist and politically risky.

That tension between bold reform and public trust was ever-present at the summit, where his vision for inclusive, values-based capitalism was met with both optimism and scepticism, mirroring the broader national conversation about Australia’s economic future.

Regardless of how one felt, there was a good dose of curiosity (and enthusiasm) about whether this Treasurer might be the one to help Australia shift gears from lucky country to strategic power.

The Indo-Pacific Moment

Chalmers opened the conversation with a reminder: Australia is now closer than ever to the world’s economic engine. In 1960, just 18 percent of global GDP was within 10,000km of Australia. Today, that figure is double. Once a quirk of geography, proximity to the Indo-Pacific is now one of Australia’s greatest strategic advantages.

Interestingly, 50 percent of our foreign direct investment comes from the region and three-quarters of our trade flows through it. That message clearly confirms we are no longer on the periphery; we are central to one of the most dynamic theatres of global growth.

“Rather than turning inwards with tariffs, we’ve chosen to build better relationships in the region to make us more resilient,” Chalmers said with his trademark calm authority and strategic clarity.

The Treasurer framed this decade as a strategic inflection point.

Australia, he argued, was at a crossroads. Whether we become a country that competes on capability or falls behind in a fragmented, protectionist world depends on the choices we make right now.

Five Forces, One Mission

When asked what structural changes were essential if Australia was to seize the opportunity in front of it, the Treasurer’s answer was expansive but anchored in defined areas: technology, energy transition, ageing populations, shifting industrial bases, and rising geopolitical uncertainty.

Each of these “forces”, he noted, were reshaping economies globally. The question is not whether they will arrive, but whether Australia will be prepared.

“Our economy in 20 years will look nothing like it did 20 years ago,” Chalmers pointed out. “Our job is to catch up, keep up and lead, and to make sure we use that change to lift living standards.”

Few topics loomed as large as AI, which Chalmers called “the most transformative influence on our economy in our lifetime.”

He rejected extreme positions. Letting AI rip without guardrails was dangerous, he argued, while pretending we could block its rise was fantasy. Instead, he proposed a uniquely Australian middle path. An AI Capability Plan will be released by the end of the year, focusing on building local expertise, attracting investment in data infrastructure, and ensuring that AI benefits were shared across sectors and communities. The goal is to maximise upside — productivity, participation, innovation — while minimising harms.

“We’re thinking about three goals,” Chalmers said. “Capturing economic upside, ensuring benefits are spread, and protecting people.”

“Australia has real advantages in a region where infrastructure, talent and trust are the new frontiers of economic power. Stable institutions, energy and water availability, legal clarity; all the things that matter to global tech investors.”

The Treasurer was optimistic that Australia could become a serious player in AI and not a mere user of offshore systems.

From Resources to Ideas

When pressed on innovation and why Australia hadn’t historically scaled its breakthroughs into global commercial powerhouses, Chalmers acknowledged the gap but offered a reframe.

“We sometimes forget the big stories we have already written such as Wi-Fi, spray-on skin, solar tech from UNSW,” he said. “Yet the next chapter must be about scale, speed and systemisation.”

The Treasurer pointed to Australia’s top-ranked universities as a foundation for becoming “a bigger player in the world of ideas” and spoke of international education not just as a $40 billion export, but as a channel for talent, human capital and cross-border collaboration.

His view was it’s time to move beyond the caricature of Australia as a resources-only economy.

“Resources are crucial, and they will remain so, especially with critical minerals in the energy transition. But we must be resources plus,” he said.

Optimism and Abundance: Not Naivety, but Urgency

When asked by an audience member why he hadn’t used the words optimism and abundance, which often feature in his speeches, Chalmers smiled and responded directly.

“I am optimistic about the future of our country and our economy,” he said.

“Not naïve, I see the challenges, but I don’t think we give ourselves enough credit. Australia has achieved rare macroeconomic balance. Inflation is easing, unemployment is low, growth is sustained and yet, the task ahead remains large: boosting productivity, ensuring budget sustainability, and building greater economic resilience.”

His optimism flows into what he calls the abundance agenda. It’s a philosophy that sees overregulation not as safety, but as a bottleneck, one that blocks homes, clean energy projects, infrastructure and industry growth. He argued for regulatory reform that’s smarter, faster and mission focused.

“We need to knock off what’s unnecessary or duplicative. We need to get cracking,” he said.

The government’s “single front door” initiative, designed to guide major investors through approval pathways, has now moved into pilot phase. Alongside it, 500 nuisance tariffs have been removed, and foreign investment approval processes have been streamlined.

“We want to be a destination of choice for capital,” Chalmers said. “And we’re prepared to change policy meaningfully to make that happen.”

This open-for-business mindset stood in contrast to the rising economic nationalism elsewhere. He pointed out how Australia was choosing the opposite path — doubling down on engagement, signalling certainty, and aligning its reforms with regional interest.

Values-Based Capitalism for a Complex Region

The conversation concluded with a question that sits at the heart of diplomacy in the Indo-Pacific: how can a values-based economic model function across such a diverse region?

Chalmers was ready: “Australia’s Southeast Asia Economic Strategy is grounded in the principle that each country must be engaged on its own terms. Our relationships with each economy are very different. They require dedicated, bespoke work,” he said.

“Values-based capitalism is not about imposing ideology, it is about design, better markets, improved communication between business and government, longer-term thinking and shared prosperity.

“We want our communities, and our friends in the region, to be the primary beneficiaries, not the victims, of global change.”

Leadership That Listens, Reform That Builds

Chalmers held his ground with clarity and composure in a summit rich with competing ideas and political crosscurrents. Whether or not you agree with his economic model, there is little doubt he is attempting to chart a future-oriented path that seeks to align policy, productivity and purpose.

And while sceptics remain, as they should in any healthy democracy, the Treasurer’s willingness to tackle complexity head-on, to communicate with candour and to build cross-border consensus speaks to a deeper question about the kind of leadership Australia wants in the decades ahead.

Because in the end, the real test of Chalmers’ agenda is not in rhetoric but rather outcomes. As he reminded us, the time to act is now: “We have a big chance to get this right.”